Books (me)

- Anxious People, Fredrik Backman

- Life Before Man, Margaret Atwood

- A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, Dave Eggers

- Stone Mattress: Nine Tales, Margaret Atwood

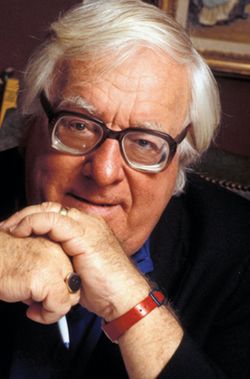

- Quicker than the Eye: Stories, Ray Bradbury

- Weimar German: Promise and Tragedy, Eric D. Weitz

- The Daughter of Time, Josephine Tey

- Spies: A Novel, Michael Frayn

- The Further Misadventures of Ellery Queen, Josh Pachter and Dale C. Andrews, eds.

- The Brooklyn Follies, Paul Auster

- The Heroine with 1,001 Faces, Maria Tatar

- The Six: The Lives of the Mitford Sisters, Laura Thompson

- Magic for Beginners, Kelly Link

- We Are Not Alone, James Hilton

- Capote’s Women, Laurence Leamer

- Britt-Marie Was Here, Fredrik Backman

- Picnic at Hanging Rock, Joan Lindsay

- The Secret of Hanging Rock, Joan Lindsay

- Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury

The only dud in the year’s batch was Capote’s Women, which I bought without a second thought, as I am fascinated by the enigmatic, glamorous beings featured, such as Babe Paley, Carol Matthau, Oona Chaplin, Pamela Harriman, Slim Keith, and Gloria Vanderbilt. The ilk of these quintessential mid-twentieth-century women may never be seen again, as their shadowy origin stories and carefully curated personas would evaporate and shrivel in the harsh, cruel glare of contemporary tell-everything-all-the-time media. I am endlessly intrigued by their collective ambiguous position along the spectrum of female protaganism: canny heroines of self-creation like Gypsy Rose Lee and Sarah Bernhardt, or languid wastrels alongside the profligate Duchess of Windsor and the venomous Alice Roosevelt Longworth? Ultimately, they toil not and neither do they spin, so wherein lies their charm? I was hoping this book would provide clues: it did not, and I hate-read my way through it, loathing everything from its cutesy chapter titles punning on the focal swan (“Slim Pickings,” “Gloria in Excelsis”); to its editor, who couldn’t even string together a cohesive parallelism in the book’s subtitle (“A True Story of Love, Betrayal, and a Swan Song for an Era”) and certainly couldn’t convince the author toward a more coherent organization of his subject (telling Capote’s biography within the confines of the various swan chapters led to many a lame or nonexistent transition and ultimately distracted and detracted from the narrative’s already weak thrust); to its lack of primary sources (!); to the book designer’s decision not to include running chapter heads; to its glib summations, archly gossipy tone, inane generalizations (“Slim had other good things happening that had to with the world around her.”) — argh!! this book is simply terrible, and it is a sin that it’s a bestseller; it isn’t the least bit compelling or interesting or slickly well-written.

All the other choices were most fine, particularly the discovery of the Nordically optimistic works of Fredrik Backman: he has a glum outlook on humanity but a deep affection for people, especially peculiar, decidedly off or oddball, people. And his writing is funny as hell:

The older couple had been married for a long time, but the younger couple seemed to have only gotten married recently. You can always tell by the way people who love each other argue: the longer they’ve been together, the fewer words they need to start a fight.

She had surprised herself back there, had lost control, felt things. For anyone else that might have been vaguely uncomfortable, like when you discover you’re starting to share the same taste in music as your parents, or biting into something you think is chocolate but turns out to be liver pâté, but for Zara it unleashed a feeling of complete panic.

and also quietly profound:

People need bureaucracy, to give them time to think before they do something stupid.

and profoundly affecting:

He just sat quietly in the waiting room and held his dad until it was impossible to tell whose tears were running down his neck. The following morning they were angry at the sun for rising, and couldn’t forgive the world for living on without her.

Plus I love love love the design of his books (that wonderful attenuated title font, perhaps Lemon Yellow Sun? and, in Britt-Marie Was Here, the use of little doodle icons as chapter titles). Even when the plot in Britt-Marie didn’t go the way I editorially thought best, I forgave Backman, because it’s a special kind of comfort read that I find very satisfying, morally, intellectually, and humanely.

The other reads were reliably smart and engaging. I was very happy to rediscover old friends from The Robber Bride in Atwood’s Stone Mattress collection (“I Dream of Zenia with the Bright Red Teeth”). I was surprised on two counts: one, the Auster book was the most upbeat, cheerful Auster I’d ever read; two, the Kelly Link stories revealed that maybe you could have too much Link at a time. And while I didn’t actively dislike it, I did grow weary of the Eggers book and found it increasingly difficult to get behind or past the narrator.

Books (Steve)

- Howard Hughes, Donald Barlett

- Black Dahlia, James Ellroy

- Anxious People, Fredrik Backman

- The Big Blowdown, George Pelecanos

- Indian Killer, Sherman Alexie

- The Daughter of Time, Josephine Tey

- Harold, Steven Wright

- Jesus’ Son, Denis Johnson

- Five Carat Soul, James McBride

- The Life and Times of Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett

- Spies: A Novel, Michael Frayn

- Ancestors and Others, Fred Chappell

- Bright and Guilty Places, Richard Rayner

- Killer of the Flower Moon, David Grann

- The Night in Question, Tobias Wolff

- Talking God, Tony Hillerman

- Fire in the Hole, Elmore Leonard

- Picnic at Hanging Rock, Joan Lindsay

Steve’s favorite of these was Killer of the Flower Moon, which kept him constantly questioning whether this-too-fantastic-to-be-true story was actually a novel. He also really liked Harold, which very much has the voice of Steven Wright’s standup. He was most pleased to discover both Tobias Wolff and Tony Hillerman; they really spoke to him and more books by both are in the stack for this coming year’s reading. Also in the pile for next year are more by James McBride, who is always a keen pleasure. He really enjoyed reading Pat Garrett’s account of the life and legend of Billy the Kid; so much has been written about this notorious outlaw, reading something by a contemporary — and a former friend and his executioner at that — gave a unique, perhaps truer, perspective. He also liked reading about the fascinating and nutty Howard Hughes.

Theater, Dance, and Concerts

- Yes, I Can Say That! (59E59)

- Camelot (Lincoln Center)

- Best Friends (Rattlestick Theatre)

- The Harder They Come (Public Theater)

- Hidden (The Playwrights’ Gate)

- Copland Dance Episodes (New York City Ballet)

- The Beautiful Lady (La Mama)

- Jeff Daniels

- Flamenco Vivo Carlota Santana (Joyce Theater)

- Downtown Urban Arts Festival

- Players Theatre 12th Annual Short Play and Musical Festival

- Psychic Self-Defense (HERE)

- Dracula—in Denver!

- Tricykle (La Mama)

- Jump Start (La Mama)

- A Celebration of Ray Bradbury Hosted by Neil Gaiman (Symphony Space)

- Pair (No. 11 Productions, 59E59)

- Scene Partners (Vineyard Theatre)

- Adrift (Happenstance Theater, 59E59)

- Some Like It Hot (Shubert Theatre)

SO nice to get to go to the theater so much! Several of our outings were to see the girls, and these were uniformly wonderful: Yael tough and funny in Best Friends, which was performed at alternate performances in English and Hebrew; Julie as Coosje van Bruggen in Pair, which is achingly lovely, particularly the scene where Coosje and Claes (Oldenburg) mutually age each other through a bit of tender theater magic. And of course Sarah’s many Dracula productions to the point where I have teased her that her obituary will begin “Sarah Congress, writer of the beloved ten-minute play Dracula—in Denver!…,” but her work is all so fun and gossamer and it is great to see her getting the professional productions her work deserves.

Just like old times, we went to see a show on Martin’s recommendation, and Some Like It Hot was a delight. Frothy and fun; we were glad to make it our holiday treat.

All the puppets we went specially to see this year at La Mama were something of a washout: too much foregrounding of the puppeteers and not enough immersion in illusion. This criticism applied to HERE’s Psychic Self-Defense as well; it was good, but not great, and it did not take me places outside myself. But then, unlooked for, we happened on Happenstance’s Adrift at 59E59; they, like Julie’s No.11, are a resident company, and share the same upbeat, creative, moral vibe. A most delightful and smart production, based on the works of Hieronymus Bosch — but so funny and so multifaceted with music and mime and silliness and prestidigitation and, yes, puppets. Also at 59E59, it was great fun to laugh with Judy Gold; at the Vineyard, it was a privilege to laugh with and be moved by Diane Wiest.

The two dance outings were outstanding. I have written elsewhere about the flamenco; the ballet was wonderful. Bright and beautiful and glorious. I have no words, but I did have tears.

Jeff Daniels at Beacon was our only concert (Steve says we’re getting old, and the people we like don’t get around much), and he was just as ornery and funny and smart and passionate as we had remembered from all those years ago at the Barns at Wolf Trap. Some of the same stories, too, but so funny they are worth the retelling. I particularly liked the stories he told and the songs he sang around Lanford Wilson: it’s a great thing to have known when you were very young that something or someone very special was happening for you. Wilson asking Daniels to set a poem of his to music must have been momentous at the time; the result is just as rueful and smart as a Wilson play.

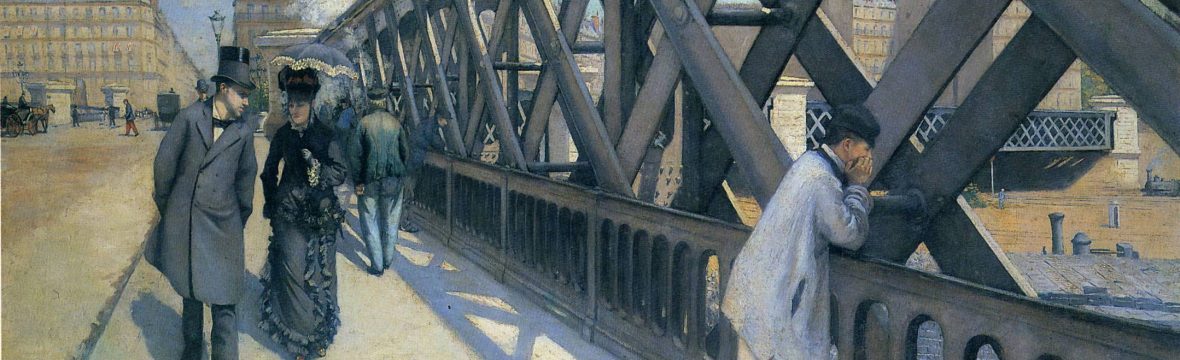

Should also mention a very satisfying trip to the Whitney to see a wonderful Edward Hopper exhibit. Always so nice to spend time communing with Hopper.

Movies

Our Letterboxd diary has 219 movies; these are the ones we saw in theaters:

- Tar

- The Lost King

- You Hurt My Feelings

- 2023 Oscar Nominated Shorts

- Asteroid City

- Barbie

- Oppenheimer

- Passages

- The Others

- Killers of the Flower Moon

- Anatomy of a Fall

- The Holdovers

- It’s A Wonderful Life

- Poor Things

So many great movies this year, with such female prominence — in the best possible way. Women freed not only of non-Bechdel considerations of male object status, but given the opportunity to be just as shitty and complex and maddening and messy as a multifaceted male protagonist.

Steve’s favorite in-theater movies, in order: Killers of the Flower Moon, Oppenheimer, Poor Things. Mine: Poor Things, Anatomy of a Fall, Tar. We both disliked (me, intensely) The Holdovers, which we found inauthentic and uncompelling.

We saw many new-release movies at home, largely because they disappear so quickly from theaters these days; these included May December, which was staggering; Theater Camp, which was endearing and so funny; Women Talking, which was a huge disappointment: I love Sarah Polley’s work, but this seemed so intent on ticking every “woke” checkbox that I could not discern its soul; and Three Thousand Years of Longing, which was rather amazing, a fairy tale.

We found — on Hulu, Max, Netflix, Amazon, Kanapy, or Mubi — an amazing variety of fantastic movies, old and new. Here are the ones that blew us away, took us outside ourselves, and left us hungry for more by a given actor or director:

- The Train (1964, directed by John Frankenheimer and owned by Burt Lancaster; a staggeringly great antiwar war film, explaining the difference between art and life)

- Hester Street (1975, directed by Joan Micklin Silver and with an astonishing performance by Carol Kane of a rapidly assimilating Russian Jew in the Lower East Side)

- Pig (2021, featuring a breathtakingly restrained Nicolas Cage performance)

- Petite Maman (2021, an achingly lovely dreamlike tale about mothers and daughters and childhood)

- In the Aisles (2018, a German revelation about life in a Costco-like warehouse store featuring not only Franz Rogowski, our new favorite young actor; but also Sandra Hüller, a fascinating actress peer to Juliette Binoche and Tilda Swinton; and also Peter Kurth, the mesmerizing Bruno in Babylon Berlin)

- Headhunters (2011, a delicious Danish noir thriller filled with myriad unexpected twists and turns)

- Shit Year (2010, a stark, shocking, hilarious ride grounded by a fantastic Ellen Barkin)

- The Vast of Night (2019, poetic, delicate, nostalgic, and real)

- What Happened Was… (1994, directed by and starring Tom Noonan; everything terrible and potentially wonderful about trying to connect)

- Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975; see earlier description)

- People on Sunday (1930; a Weimar Republic idyll/semi-documentary created by, among others, Robert Siodmak and Billy Wilder)

- This Boy’s Life (1993; a true story which turned us on to Tobias Wolff and reaffirmed our admiration for Ellen Barkin; also staring De Niro and DiCaprio)

- Alice in the City (1974, directed by Wim Wenders, which brought me to tears not because of dialogue or situation, but just pure feeling: the loneliness, the isolation, with whatever connections the protagonists made diminished by the uncaring passing scenery)

- After Life (1998, directed by Hirokazu Kore-eda, whose premise of if you could take one memory with you into the next life, what would it be? is undercut by the clumsiness with which that memory is to be fixed, all adding up to the Our Town injunction of pay attention, life only goes by once)

- Decision to Leave (2022; a haunting noir directed by Park Chan-wook)

Mubi’s organization encourages deep dives and wild deviations; through it, we found a lot of exciting movies and artists we would not otherwise have encountered, notably Peter Tscherkassky, whose incredible under-three-minute short L’arrivée can be seen — no, experienced — on Vimeo. Other intriguing hits we chanced on were the feminist marvel from Steven Soderbergh Haywire, the sweet and sad Undine, Wander Darkly, ivans xtc. with its bravura performance from Danny Huston, Wim Wenders The Million Dollar Hotel, Henry Fool, The Human Factor, Michael Almereyda’s crazy Twister with the as-usual-unforgettable Harry Dean Stanton, Peter Weir’s eerie The Last Wave, and The Girl Chewing Gum.

During the year, we filled in some missing classics or standards one or both of us had not previously seen; these included Midnight Run, Heat, The Trip to Greece, Haneke’s The White Ribbon, Lanthimos’s Dogtooth, My Brilliant Career, Serpico, The Ruling Class, Christopher Strong, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, Mister Roberts, and Berlin: Symphony of a Great City.

We also unearthed some surprising gems from old Hollywood. Lubitsch’s Design for Living might still be ahead of its time, so daring is its matter-of-fact central thrupple of Gary Cooper (!), Miriam Hopkins, and Fredric March; 1955’s The Glass Slipper is a refreshingly tart and crisp Cinderella with little magic aside from its casting coups of Leslie Caron and Estelle Winwood; Douglas Sirk’s Lured is a potboiler noir with a sexy and sassy and fearless Lucille Ball as a girl detective alongside the impeccably suave George Sanders, and a quite quite mad Boris Karloff; the surprise to Anatole Litvak’s Cold War The Journey was that it was essentially a remake of The King and I — who else but Yul Brynner could be so menacing, so cold, so merciless and still sing Russian folk songs?

Finally, we saw numerous first-run documentaries; these are the highlights.

- Albert Brooks: Defending My Life

- Being Mary Tyler Moore

- Sr.

- My Old School

- Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time

- The Meaning of Hitler

- The Booksellers

- Too Funny to Fail: The Life & Death of the Dana Carvey Show

- Dad’s Stick

- The Day After Trinity

TV

The best of our TV viewing from 2023:

- New Tricks

- Case Histories

- Kleo

- The Diplomat

- Good Omens

- The Bear

Another highlight besides these was The Kingdom. I think we first subscribed to Mubi to watch Lars von Trier’s original ’90s seasons and the 2022 final season, which was indeed a weird and wacky Danish counterpart to Twin Peaks — more absurdist and less otherworldly, but decidedly funnier than we would have expected from the confrontational von Trier, particularly in his Hitchcockesque post-show wrap-ups.

Another auteur’s TV venture fell quite flat with us. Wes Anderson’s Roald Dahl’s shorts on Netflix (“The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar,” “The Swan,” “The Rat Catcher,” and “Poison”) left us cold — which well might have been the intent, so distanced and distancing were they, with actors (all male) talking to the camera and narrating the action and sometimes using make-pretend theater props and sometimes being quite literal and always flat and two dimensional. We love Anderson’s long-form movies (particularly The French Dispatch), but are less enamored of his animation; as here, the humanity is harder to find.

Field Trips

- Tied for first place: Four September days (albeit HOT ones) in Cape Ann — a triumphant, relaxing, and most lovely post-COVID return to a place that had made Steve and me so happy four years ago — with all three girls this time. We had very few scheduled items: a whale-sighting cruise (which yielded, surprisingly, no whales! but did elicit (1) a free pass for a future cruise and (2) renewed gratitude for the wondrous experience we had had in 2019), and a nighttime spiritualism tour of Hammond Castle. Mostly what we felt was less a desire to broaden horizons than to narrow them, to stay extremely close to our Rockport/Gloucester base. Many many happy hours shopping, eating, walking, being.

- Tied for first place: Hudson Valley — Kingston, Rhinebeck, Woodstock, Hyde Park, Saugerties. We took Sarah for three days upstate in April, retracing our steps at Hyde Park, but then taking delicious, unscheduled time in several other little towns, each featuring a fantastic bookstore, lots and lots of charming shops, and beautiful scenery. We had a beautiful picnic in Saugerties, and a lovely half-day in Woodstock, which was fun, hip, friendly, and interesting. Can’t wait to go back.

- Also-rans, also delightful: Richmond in May, November, and December to see Danny, Emily, Ollie, and the vivacious Alice. The last trip, completed last week, not so much fun, given horrendous, unspeakable traffic. Also a quick day jaunt to Newtown, PA, which sounded more exciting than it was, but still good to go. And long ambling strolls to and from the 35th Street pier and 59th Street theater, and some nice cross-Village walks.

We should also note a few quite lovely field trips by others to us: we had a wonderful time seeing Tracey and Guy last month and in the spring; Jeannie and Bob and Jenny in August; and Kim in September.

Food and Restaurants

- Paradigm-shifting highlight: the new Ninja 7-in-1 grill, which includes a smoker and an air fryer; new culinary worlds were opened

- Exciting new effort: our herb garden on the deck (which let us make pesto, which we don’t even like)

- Best of the best new creations: smoked salmon, candied pecans, focaccia, manque roux (lovely spicy corn), pan-roasted potatoes (steamed and then roasted: soft on the inside and super crispy on the outside), spiced apple rings (now that these are no longer commercially produced)

- Feasts: Both annual feasts — Thanksgiving and Seven Fishes — were peak, especially because everyone could come this year (no COVID)

- New finds: Dolce Fantasia in Asbury; Knickerbocker Grill in the city; Uncle Giuseppe’s Marketplace, almost camp in its excess

- Old returns: Monte’s Trattoria in the Village, still old-school yummy although bittersweet without Giovanni

- Loss: A Little Bit of Cuba in Freehold